In the midst of reading Proust, I picked up a quick read from the library, Tweak by Nic Sheff. I recalled hearing Sheff on NPR, along with his father, discussing his memoir, subtitled "Growing up on Methamphetamines." I read the book in one night with mild interest. Although Sheff is an okay writer, poetic at times with an apparently near photographic memory, he lacks perspective and his attempts are often heavy-handed (Sheff names the homeless kid who hooks him up with meth on his first major relapse Destiny, etc etc etc), I didn't really gain any insight or learn anything new about meth addiction from his memoir.

Sheff grew up in privileged circles in San Francisco and L.A. - where every friend is the kid of someone famous and all your liberal parents have houses on the ocean in Point Reyes. Having grown up in L.A. and lived in the Bay Area, I could relate. Sheff's settings were all familiar to me and his characters accurate enough, though sketchy.

The descriptions of the mass quantities of drugs Sheff was putting into his body were kind of mind boggling. Lately I've been thinking about how tiny our bodies really are - not much more than a torso filled with vital organs. I can't imagine shooting meth and coke hour after hour, day after day, for months straight. While Sheff does a pretty good job describing the mutilation of his body over time, he offered little insight into the mind of an addict.

The second half of the book delves into his 12 step recovery, which I sped-read with little to no interest, until he relapses again with his girlfriend Zelda and eventually ends up in a 3 month rehab program where he confronts his past as a co-dependent tweaker and street prostitute, and then (supposedly) sobers up for good. In one section near the end of the book Sheff describes a therapy session using dolls. His mom is a plastic alligator, his dad a teddy bear, his step-dad a T-rex. "After I finish," Sheff writes, "people in the group are encouraged to point out what they notice regarding color similarities and placement -- whatever. This one girl with a shaved head notices that I've used the same animal to represent Zelda and my mom. They are also lying in the same position. Someone else points out that they are even the same color. It is just a coincidence, but it does make me think." In the end, I guess I had a hard time buying his sunshine-lite hopes for the future, given the superficial self-awareness Sheff only seems capable of. I hope for the best for him.

On topic, I saw a crappy documentary, "American Meth," recently, which offered even less insight on the subject than Sheff's book. Near the end of the film, though, for about 15 minutes the documentary inexplicably strays from straight interviews and archival footage to follow a couple of tweakers living in a trailer with their three kids. As mom and dad get high, pass out, and scream at each other, their two year old daughter fends for herself. There is a haunting scene in which the two year old shuffles through the pitch black, pre-dawn trailer in search of food. The images reminded me of the scene in ET when a drunken ET waddles to the fridge in search of beer or Reeses Pieces. The refrigerator door opens, silhouetting this little baby wearing nothing but a sagging diaper, her hair a giant mass of tangles and mats. Holding her empty baby bottle in one hand, she reaches in the fridge and clumsily lugs a heavy, two gallon jug of milk from the shelf. If she doesn't fill her own bottle, the narrator tells us, no one will. Several hours later, her parents still passed out, the toddler has scavenged a half eaten bag of microwave popcorn out of the garbage for breakfast. Later still, dirt perpetually smeared across her cheeks and over her distended stomach, the baby girl tiptoes over some precariously stacked sofa cushions as her parents scream at each other in the background. Suddenly she leaps off the top of the cushions, she's airborne, and then she lands on a broken armchair with a happy grin.

This little toddler, all alone in a crowded meth shack, but surviving and even having some fun, is an amazing example of how resilient children can be.

She appears at the end of this trailer, at -0.08 seconds.

Sunday, November 1, 2009

a dream more lucid

For me, in the following passage Proust perfectly describes the pleasure of reading, how a novel enables its reader to transcend her own ordinary existence, to transcend time. Unwittingly, or wittingly?, he captures here the essence of what it has been like to read In Search of Lost Time (life imitating art imitating life) and what, as writers and readers, we aspire to achieve.

After this central belief, which moved incessantly during my reading from inside to outside, toward the discovery of the truth, came the emotions aroused in me by the action in which I was taking part, for those afternoons contained more dramatic events than does, often, an entire lifetime. These were the events taking place in the book I was reading; it is true that the people affected by them were not "real," as Françoise said. But all the feelings we are made to experience by the joy or the misfortune of a real person are produced in us only through the intermediary of an image of that joy or that misfortune; the ingeniousness of that first novelist consisted in understanding that in the apparatus of our emotions, the image being the only essential element, the simplification that would consist in purely and simply abolishing real people would be a decisive improvement. A large part perceived by our senses, that is to say, remains opaque to us, presents a dead weight which our sensibility cannot lift. If a calamity should strike him, it is only in a small part of the total notion we have of him that we will be able to be moved by this; even more, it is only in a part of the total notion he has of himself that he will be able to be moved himself. The novelist's happy discovery was to have the idea of replacing these parts, impenetrable to the soul, by an equal quantity of immaterial part, that is to say, parts which our soul can assimilate. What does it matter thenceforth if the actions and the emotions of this new order of creatures seem to us true, since we have made them ours, since it is within us that they occur, that they hold within their control, as we feverishly turn the pages of the book, the rapidity of our breathing and the intensity of our gaze. And once the novelist has put us in that state, in which, as in all purely internal states, every emotion is multiplied tenfold, in which his book will disturb us as might a dream but a dream more lucid than those we have while sleeping and whose memory will last longer, then see how he provokes in us within one hour all possible happinesses and all possible unhappinesses just a few of which we would spend years of our lives coming to know and the most intense of which would never be revealed to us because the slowness with which they occur prevents us from perceiving them (thus our heart changes, in life, and it is the worst pain; but we know it only through reading, through our imagination: in reality it changes, as certain natural phenomena occur, slowly enough so that, if we are able to observe successively each of its different states, in return we are spared the actual sensation of change).

...For even if we have the sensation of being always surrounded by our own soul, it is not as though by a perpetual prison: rather, we are in some sense borne along with it in a perpetual leap to go beyond it, to reach the outside, with a sort of discouragement as we hear around us always that same resonance, which is not an echo from outside but the resounding of an internal vibration.

After this central belief, which moved incessantly during my reading from inside to outside, toward the discovery of the truth, came the emotions aroused in me by the action in which I was taking part, for those afternoons contained more dramatic events than does, often, an entire lifetime. These were the events taking place in the book I was reading; it is true that the people affected by them were not "real," as Françoise said. But all the feelings we are made to experience by the joy or the misfortune of a real person are produced in us only through the intermediary of an image of that joy or that misfortune; the ingeniousness of that first novelist consisted in understanding that in the apparatus of our emotions, the image being the only essential element, the simplification that would consist in purely and simply abolishing real people would be a decisive improvement. A large part perceived by our senses, that is to say, remains opaque to us, presents a dead weight which our sensibility cannot lift. If a calamity should strike him, it is only in a small part of the total notion we have of him that we will be able to be moved by this; even more, it is only in a part of the total notion he has of himself that he will be able to be moved himself. The novelist's happy discovery was to have the idea of replacing these parts, impenetrable to the soul, by an equal quantity of immaterial part, that is to say, parts which our soul can assimilate. What does it matter thenceforth if the actions and the emotions of this new order of creatures seem to us true, since we have made them ours, since it is within us that they occur, that they hold within their control, as we feverishly turn the pages of the book, the rapidity of our breathing and the intensity of our gaze. And once the novelist has put us in that state, in which, as in all purely internal states, every emotion is multiplied tenfold, in which his book will disturb us as might a dream but a dream more lucid than those we have while sleeping and whose memory will last longer, then see how he provokes in us within one hour all possible happinesses and all possible unhappinesses just a few of which we would spend years of our lives coming to know and the most intense of which would never be revealed to us because the slowness with which they occur prevents us from perceiving them (thus our heart changes, in life, and it is the worst pain; but we know it only through reading, through our imagination: in reality it changes, as certain natural phenomena occur, slowly enough so that, if we are able to observe successively each of its different states, in return we are spared the actual sensation of change).

...For even if we have the sensation of being always surrounded by our own soul, it is not as though by a perpetual prison: rather, we are in some sense borne along with it in a perpetual leap to go beyond it, to reach the outside, with a sort of discouragement as we hear around us always that same resonance, which is not an echo from outside but the resounding of an internal vibration.

Monday, September 7, 2009

lost in translation

Lying in the grass in the park reading the French Pléiade edition of Proust's 'Swann's Way' translated by C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin, I remembered why I have never finished the book, though I have started it several times. Moncrieff's translation, filled with redundancies ("he himself") and characterized by purple prose was just too oldsy timesy for my taste. Proust's original, natural tone was given, by Moncrieff, an overly wordy, melodramatic, sentimental air. Moncrieff's translation of the title 'À la recherche du temps perdu' as 'Remembrance of Things Past' has even been re-translated for accuracy and the book's title is now most commonly accepted as 'In Search of Lost Time.'

I recalled how gripping, how contemporary I'd discovered Dostoevsky to be when translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. Perhaps I just needed a new translation of Marcel, as well. A friend recommended fiction author Lydia Davis' new translation and I set about researching. On a 'Reading Proust' blog, I found four versions of the famous petite madeleine scene from 'In Search of Lost Time,' in which a bite of cookie soaked in tea sets off the memory which leads to the narrator's recollections of childhood and comprise the rest of the novel. Suffice to say, I was awake into the wee hours last night, reading Lydia Davis' translation and, for the first time, finally falling in love with Proust.

From Lydia Davis's translation of Swann's Way (2003)

For many years already, everything about Combray that was not the theatre and drama of my bedtime had ceased to exist for me, when one day in winter, as I came home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, suggested that, contrary to my habit, I have a little tea. I refused at first and then, I do not know why, changed my mind. She sent for one of those squat, plump cakes called petites madeleines that look as though they have been molded in the grooved valve of a scallop-shell. And soon, mechanically, oppressed by the gloomy day and the prospect of a sad future, I carried to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had let soften a piece of madeleine. But at the very instant when the mouthful of tea mixed with cake-crumbs touched my palate, I quivered, attentive to the extraordinary thing that was happening in me. A delicious pleasure had invaded me, isolated me, without my having any notion as to its cause. It had immediately made the vicissitudes of life unimportant to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory, acting in the same way that love acts, by filling me with a precious essence: or rather this essence was not in me, it was me.

Translated by James Grieve (1982)

One winter's day, years after Combray had shrunk to the mere stage-set for my bedtime performance, I came home cold and my mother suggested I have a cup of tea, a thing I did not usually do. My first impulse was to decline; then for some reason I changed my mind. My mother sent for one of those dumpy little sponge-cakes called madeleines, which look as though they have been moulded inside a corrugated scallop-shell. Soon, depressed by the gloomy day and the promise of more like it to come, I took a mechanical sip at a spoonful of tea with a piece of the cake soaked in it. But at the very moment when the sip of tea and cake-crumbs touched my palate, a thrill ran through me and I immediately focussed my attention on something strange happening inside me. I had been suddenly singled out and filled with a sweet feeling of joy, although I had no inkling of where it had come from. The joy had instantly made me indifferent to the vicissitudes of life, inoculated me against any setback it might have in store and shown me that its brevity was an irrelevant illusion; it had acted on me as love acts, filling me with a precious essence--or rather, the essence was not put into me, it was me, I was it.

Translated by Scott Moncrieff and improved by Kilmartin and Enright (1992)

Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, except what lay in the theatre and the drama of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in winter, on my return home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent for one of those squat, plump little cakes called "petites madeleines", which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted valve of a scallop shell. And soon, mechanically, dispirited after a dreary day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shiver ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory—this new sensation having had the effect, which love has, of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me, it was me.

Scott Moncrieff's original version (1922)

Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, save what was comprised in the theatre and the drama of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in winter, as I came home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent out for one of those short, plump little cakes called 'petites madeleines,' which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted scallop of a pilgrim's shell. And soon, mechanically, weary after a dull day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate than a shudder ran through my whole body, and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary changes that were taking place. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory--this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me, it was myself.

As Proust wrote it (1913)

Il y avait déjà bien des années que, de Combray, tout ce qui n'était pas le théâtre et la drame de mon coucher, n'existait plus pour moi, quand un jour d'hiver, comme je rentrais à la maison, ma mère, voyant que j'avais froid, me proposa de me faire prendre, contre mon habitude, un peu de thé. Je refusai d'abord et, je ne sais pourquoi, me ravisai. Elle envoya chercher un de ces gâteaux courts et dodus appelés Petites Madeleines qui semblaient avoir été moulés dans la valve rainurée d'une coquille de Saint-Jacques. Et bientôt, machinalement, accablé par la morne journée et la perspective d'un triste lendemain, je portai à mes lèvres une cuillerée du thé où j'avais laissé s'amollir un morceau de madeleine. Mais à l'instant même où la gorgée mêlée des miettes du gâteau toucha mon palais, je tressaillis, attentif à ce qui se passait d'extraordinaire en moi. Un plaisir délicieux m'avait envahi, isolé, sans la notion de sa cause. Il m'avait aussitôt rendu les vicissitudes de la vie indifférentes, ses désastres inoffensifs, sa brièveté illusoire, de la même façon qu'opère l'amour, en me remplissant d'une essence précieuse: ou plutôt cette essence n'était pas en moi, elle était moi.

I recalled how gripping, how contemporary I'd discovered Dostoevsky to be when translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. Perhaps I just needed a new translation of Marcel, as well. A friend recommended fiction author Lydia Davis' new translation and I set about researching. On a 'Reading Proust' blog, I found four versions of the famous petite madeleine scene from 'In Search of Lost Time,' in which a bite of cookie soaked in tea sets off the memory which leads to the narrator's recollections of childhood and comprise the rest of the novel. Suffice to say, I was awake into the wee hours last night, reading Lydia Davis' translation and, for the first time, finally falling in love with Proust.

From Lydia Davis's translation of Swann's Way (2003)

For many years already, everything about Combray that was not the theatre and drama of my bedtime had ceased to exist for me, when one day in winter, as I came home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, suggested that, contrary to my habit, I have a little tea. I refused at first and then, I do not know why, changed my mind. She sent for one of those squat, plump cakes called petites madeleines that look as though they have been molded in the grooved valve of a scallop-shell. And soon, mechanically, oppressed by the gloomy day and the prospect of a sad future, I carried to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had let soften a piece of madeleine. But at the very instant when the mouthful of tea mixed with cake-crumbs touched my palate, I quivered, attentive to the extraordinary thing that was happening in me. A delicious pleasure had invaded me, isolated me, without my having any notion as to its cause. It had immediately made the vicissitudes of life unimportant to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory, acting in the same way that love acts, by filling me with a precious essence: or rather this essence was not in me, it was me.

Translated by James Grieve (1982)

One winter's day, years after Combray had shrunk to the mere stage-set for my bedtime performance, I came home cold and my mother suggested I have a cup of tea, a thing I did not usually do. My first impulse was to decline; then for some reason I changed my mind. My mother sent for one of those dumpy little sponge-cakes called madeleines, which look as though they have been moulded inside a corrugated scallop-shell. Soon, depressed by the gloomy day and the promise of more like it to come, I took a mechanical sip at a spoonful of tea with a piece of the cake soaked in it. But at the very moment when the sip of tea and cake-crumbs touched my palate, a thrill ran through me and I immediately focussed my attention on something strange happening inside me. I had been suddenly singled out and filled with a sweet feeling of joy, although I had no inkling of where it had come from. The joy had instantly made me indifferent to the vicissitudes of life, inoculated me against any setback it might have in store and shown me that its brevity was an irrelevant illusion; it had acted on me as love acts, filling me with a precious essence--or rather, the essence was not put into me, it was me, I was it.

Translated by Scott Moncrieff and improved by Kilmartin and Enright (1992)

Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, except what lay in the theatre and the drama of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in winter, on my return home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent for one of those squat, plump little cakes called "petites madeleines", which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted valve of a scallop shell. And soon, mechanically, dispirited after a dreary day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shiver ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory—this new sensation having had the effect, which love has, of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me, it was me.

Scott Moncrieff's original version (1922)

Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, save what was comprised in the theatre and the drama of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in winter, as I came home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent out for one of those short, plump little cakes called 'petites madeleines,' which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted scallop of a pilgrim's shell. And soon, mechanically, weary after a dull day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate than a shudder ran through my whole body, and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary changes that were taking place. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory--this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me, it was myself.

As Proust wrote it (1913)

Il y avait déjà bien des années que, de Combray, tout ce qui n'était pas le théâtre et la drame de mon coucher, n'existait plus pour moi, quand un jour d'hiver, comme je rentrais à la maison, ma mère, voyant que j'avais froid, me proposa de me faire prendre, contre mon habitude, un peu de thé. Je refusai d'abord et, je ne sais pourquoi, me ravisai. Elle envoya chercher un de ces gâteaux courts et dodus appelés Petites Madeleines qui semblaient avoir été moulés dans la valve rainurée d'une coquille de Saint-Jacques. Et bientôt, machinalement, accablé par la morne journée et la perspective d'un triste lendemain, je portai à mes lèvres une cuillerée du thé où j'avais laissé s'amollir un morceau de madeleine. Mais à l'instant même où la gorgée mêlée des miettes du gâteau toucha mon palais, je tressaillis, attentif à ce qui se passait d'extraordinaire en moi. Un plaisir délicieux m'avait envahi, isolé, sans la notion de sa cause. Il m'avait aussitôt rendu les vicissitudes de la vie indifférentes, ses désastres inoffensifs, sa brièveté illusoire, de la même façon qu'opère l'amour, en me remplissant d'une essence précieuse: ou plutôt cette essence n'était pas en moi, elle était moi.

Saturday, September 5, 2009

Banzai, Akita. Banzai!

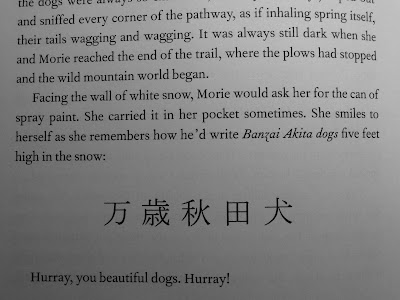

I started 'Dog Man' on Thursday night and by Saturday morning, I'd finished it. A book I didn't want to end, yet I couldn't put down, I spent two nights happily reading until past 3 a.m. Less about dogs than Japanese culture: the relationships between husbands and wives, parents, children, humans and nature, 'Dog Man' tells the story of Morie Sawataishi and his wife Kitako and spans nearly seventy years of their amazing lives. Morie rejected conventional life pursuits in order to live in Japan's harsh yet beautiful snow country, breeding and raising dogs and helping to prevent the extinction of the Akita, a four thousand year old breed of dog native to Japan whose numbers were reduced to less than sixteen after World War II. Once a sophisticate from a posh neighborhood in Tokyo, Kitako's life at times seemed an endless sentence of hard labor while Morie lived out his dreamlife, communing with his dogs and nature.

Kitako did feel lonely, but something else too -- a wistful feeling, almost beautiful, as though a part of her was waking up. She had begun to appreciate things she'd not noticed before, mountain things, the way the morning air smelled when the warm sunlight hit the earth, the way the shadows of the treetops danced on a windy afternoon. She loved the trickle of the creek behind their small house, and how the water bounced on its rocky bed. There was a solemn austerity to life in the mountains and yet... a fullness of spirit.

In the morning when the dogs bolted from their kennels and followed Morie into the woods, it seemed as though they were disappearing to a magical land, to another time. Their territory seemed boundless, miles and miles of green meadows, forests of towering cedars, and mountain peaks with sheer cliffs. The dogs craved the wild, Morie always said. It kept their instincts sharp, their spirits strong. It kept them from complacency and spiritual decline. Being in the wild reminded them who they really were -- and the amazing deeds they were meant for. It was an antidote to the convenience and comfort of modern life. Kitako wondered if people didn't need the wild too.

Castle Number 5 Town-inspired dinner: rice balls, seaweed and carrot salad, sesame kale, and Japanese eggplant

Thursday, September 3, 2009

to that which you tame, you owe your life

On a recent visit to Northern California's Sonoma County, I picked up a copy of 'Wesley the Owl: The Remarkable Love Story of an Owl and His Girl,' a fitting read given the soft owl cooing that woke me up each morning. The cover photo of Wesley as an adorable, fluffy white baby barn owl reminded me of my cat Claudie, whose new nickname is Wesley.

Since cracking the cover, I was full of owl trivia, regaling (or driving bonkers) everyone around me with fascinating tidbits: Owls mate for life -- when one partner dies, the other will often simply turn and face their tree until they, too, pass away from sorrow and loneliness; barn owls can hear a mouse's heartbeat beneath 3 feet of snow; after eating, barn owls cough up a pellet containing fur and a complete mouse skeleton; baby barn owls smell like butterscotch. Author Stacey O'Brien worked as an animal biologist at CalTech and I liked all the scientific data she included in the book. I could have done without her somewhat dubious opinions on animal activists and LA rioters, which bordered on racist, but this only slightly degraded my enjoyment of the book overall. Her appreciation of the quirks and minutiae of Wesley's personality shone through and I found her to be very enlightened about animal emotions and their ability to communicate with humans.

One of the most interesting passages in the book involved Stacey's use of mental telepathy to ease Wesley's anxiety about having his beak and talons trimmed.

Finally, more out of desperation than cleverness, on my part, I began to work with Wesley using language and imagery. Some scientists believe that animals may use some sort of mental telepathy to beam picture thoughts to communicate with each other, and experiments indicated that it does work between humans and certain animals.

For weeks, Stacey would beam Wesley visualizations of a peaceful trimming procedure. Wesley also understood many words and had a surprising grasp of the concept of time, understanding the difference between 'two days,' 'tomorrow,' and 'two hours.' Using these terms along with visualizations, Stacey began a countdown to the trimming. When the time came, Wesley hunkered down instead of flying into a panic and allowed Stacey to peacefully trim his beak and talons. Afterward, exhausted by his effort not to flee the excruciating vibrations, he fell asleep in Stacey's arms.

What a relief. I couldn't wait to tell Wendy about this on the phone. She revealed that she'd also been using this method with her horses with fantastic results. One horse in particular, named Chica, was terrified of her horse trailer. Because Wendy was moving soon, she would have to haul the mare six hours to the new place, so she spent some time sitting quietly with Chica talking about and visualizing images of the new property. When the appointed day came, Chica walked right into the trailer without Wendy even leading her. Wendy was astonished. 'It really works!' she told me.

People working wth all kinds of animals are altering their methods from those that used force and negative consequences, like spurring, hitting, shocking, or yelling, to gentler approaches of positive reinforcement. Horse whisperers are explaining their gentling techniques...Scientists are teaching language to parrots and sign language to chimpanzees.

Some researchers are also accumulating empirical evidence that animals use a form of telepathy to communicate with and understand us. Recently, Jane Goodall, who seems always to be one step ahead of everyone else in animal behavior, hosted a Discovery/Animal Planet documentary showing some of the latest experiments that demonstrate that animals use telepathic communication. Several experiments showed that some dogs can tell when their owners are about to come home, even without the cues that people had thought the animals were associating with their arrival, such as the sound of the car, the time of day, or footsteps.

The most impressive experiment, to me, was one involving an African gray parrot who had a large vocabulary and chattered to himself constantly. The owner was set up in a completely separate building, far from the parrot, and given a series of cards that neither she nor the parrot had ever seen. There were two cameras -- one on the parrot and one on the owner, with a timer running. Then the owner picked up a card and looked at the picture on it. It was a blue flower. The parrot, at that same time, began to talk to himself about blue flowers, pretty flowers. Then the owner picked up a picture of a boy looking out a car window and the parrot's chatter changed to 'Do you want to go for a ride in the car? Watch out. The window is down. Look out the window.' I am paraphrasing, but the conclusion of the experiments was that animals and humans were using telepathy.

...When humans and animals understand, love, and trust each other, the animals flourish and we humans are enlightened and enriched by the relationship...I could have forced my will on Wesley, and it would have destroyed the trust between us. Because I took some time to communicate with him, he realized that I wouldn't do anything to him without asking him first. I had allowed him to be part of the process and to maintain his dignity. Our relationship changed. Going through this together awakened a deeper bond of trust.

I have to admit I skipped the next-to-last chapter of the book titled 'The End' that described Wesley's death. But then again, I also change the channel when, during a nature program, winter or drought sets in.

Since cracking the cover, I was full of owl trivia, regaling (or driving bonkers) everyone around me with fascinating tidbits: Owls mate for life -- when one partner dies, the other will often simply turn and face their tree until they, too, pass away from sorrow and loneliness; barn owls can hear a mouse's heartbeat beneath 3 feet of snow; after eating, barn owls cough up a pellet containing fur and a complete mouse skeleton; baby barn owls smell like butterscotch. Author Stacey O'Brien worked as an animal biologist at CalTech and I liked all the scientific data she included in the book. I could have done without her somewhat dubious opinions on animal activists and LA rioters, which bordered on racist, but this only slightly degraded my enjoyment of the book overall. Her appreciation of the quirks and minutiae of Wesley's personality shone through and I found her to be very enlightened about animal emotions and their ability to communicate with humans.

One of the most interesting passages in the book involved Stacey's use of mental telepathy to ease Wesley's anxiety about having his beak and talons trimmed.

Finally, more out of desperation than cleverness, on my part, I began to work with Wesley using language and imagery. Some scientists believe that animals may use some sort of mental telepathy to beam picture thoughts to communicate with each other, and experiments indicated that it does work between humans and certain animals.

For weeks, Stacey would beam Wesley visualizations of a peaceful trimming procedure. Wesley also understood many words and had a surprising grasp of the concept of time, understanding the difference between 'two days,' 'tomorrow,' and 'two hours.' Using these terms along with visualizations, Stacey began a countdown to the trimming. When the time came, Wesley hunkered down instead of flying into a panic and allowed Stacey to peacefully trim his beak and talons. Afterward, exhausted by his effort not to flee the excruciating vibrations, he fell asleep in Stacey's arms.

What a relief. I couldn't wait to tell Wendy about this on the phone. She revealed that she'd also been using this method with her horses with fantastic results. One horse in particular, named Chica, was terrified of her horse trailer. Because Wendy was moving soon, she would have to haul the mare six hours to the new place, so she spent some time sitting quietly with Chica talking about and visualizing images of the new property. When the appointed day came, Chica walked right into the trailer without Wendy even leading her. Wendy was astonished. 'It really works!' she told me.

People working wth all kinds of animals are altering their methods from those that used force and negative consequences, like spurring, hitting, shocking, or yelling, to gentler approaches of positive reinforcement. Horse whisperers are explaining their gentling techniques...Scientists are teaching language to parrots and sign language to chimpanzees.

Some researchers are also accumulating empirical evidence that animals use a form of telepathy to communicate with and understand us. Recently, Jane Goodall, who seems always to be one step ahead of everyone else in animal behavior, hosted a Discovery/Animal Planet documentary showing some of the latest experiments that demonstrate that animals use telepathic communication. Several experiments showed that some dogs can tell when their owners are about to come home, even without the cues that people had thought the animals were associating with their arrival, such as the sound of the car, the time of day, or footsteps.

The most impressive experiment, to me, was one involving an African gray parrot who had a large vocabulary and chattered to himself constantly. The owner was set up in a completely separate building, far from the parrot, and given a series of cards that neither she nor the parrot had ever seen. There were two cameras -- one on the parrot and one on the owner, with a timer running. Then the owner picked up a card and looked at the picture on it. It was a blue flower. The parrot, at that same time, began to talk to himself about blue flowers, pretty flowers. Then the owner picked up a picture of a boy looking out a car window and the parrot's chatter changed to 'Do you want to go for a ride in the car? Watch out. The window is down. Look out the window.' I am paraphrasing, but the conclusion of the experiments was that animals and humans were using telepathy.

...When humans and animals understand, love, and trust each other, the animals flourish and we humans are enlightened and enriched by the relationship...I could have forced my will on Wesley, and it would have destroyed the trust between us. Because I took some time to communicate with him, he realized that I wouldn't do anything to him without asking him first. I had allowed him to be part of the process and to maintain his dignity. Our relationship changed. Going through this together awakened a deeper bond of trust.

I have to admit I skipped the next-to-last chapter of the book titled 'The End' that described Wesley's death. But then again, I also change the channel when, during a nature program, winter or drought sets in.

Monday, July 20, 2009

revelations

To D- Dead by Her Own Hand

My dear, I wonder if before the end

You ever thought about a children's game-

I'm sure you must have played it too - in which

You ran along a narrow garden wall

Pretending it to be a mountain ledge

So steep a snowy darkness fell away

On either side to deeps invisible;

And when you felt your balance being lost

You jumped because you feared to fall, and thought

For only an instant: That was when I died.

That was a life ago. And now you've gone,

Who would no longer play the grown-ups' game

Where, balanced on the ledge above the dark,

You go on running and you don't look down

Nor ever jump because you fear to fall.

-Howard Nemerov (Diane Arbus' brother)

My dear, I wonder if before the end

You ever thought about a children's game-

I'm sure you must have played it too - in which

You ran along a narrow garden wall

Pretending it to be a mountain ledge

So steep a snowy darkness fell away

On either side to deeps invisible;

And when you felt your balance being lost

You jumped because you feared to fall, and thought

For only an instant: That was when I died.

That was a life ago. And now you've gone,

Who would no longer play the grown-ups' game

Where, balanced on the ledge above the dark,

You go on running and you don't look down

Nor ever jump because you fear to fall.

-Howard Nemerov (Diane Arbus' brother)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)